Efficient production… is a result not of having better resources but in knowing more accurately the relative productive performance of those resources.

Alchian and Demsetz (1972)

“Management matters.” This is the key message that has been long coming out of the empirical literature on managerial quality for some time. Bloom and Van Reenen’s 2007 paper famously showed that as much as 30 per cent of the difference in firm level productivity can be explained by differences in managerial quality.

Most of these studies have focussed on the impact management has on firm productivity, but increasingly the focus has shifted to the importance to innovation. This, for example, from the Institute for Competitiveness and Prosperity:

Strong management also provides the necessary pressure that drives the demand for innovation. As customers, good managers drive the requirement for innovation by suppliers; this, in turn, drives overall demand for innovation. Good managers also pressure industry rivals to be innovative in order to succeed – in fact, to survive.

In a 2013 study, ISED used firm level data to explore the significance of management practices and firm performance. Their “most important result” was the positive correlation between management practices and innovation — a result that held even when accounting for other variables such as firm size, structure and competition. (Analyses of Australiandata have resulted in similar findings.)

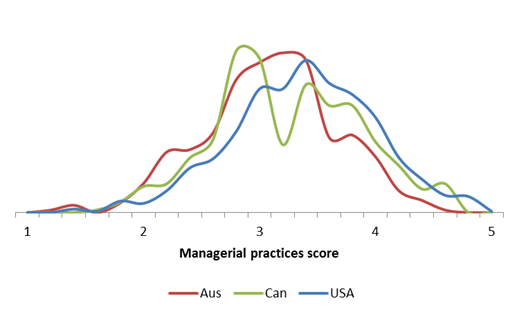

International comparisons of management capability place the average Canadian (manufacturing) firm marginally ahead of the average Australian; but both sit some ways back from the US. Data collected through the World Management Survey shows that the top 50 per cent of US firms for instance, are better managed than the bottom 75 per cent of Australian firms, and the bottom 60 per cent of Canadian.

While the average Australian and Canadian firm might not be too different, the distribution of managerial quality across firms shows some striking differences.

The World Management Survey ranks firms’ competencies on a scale of 1-5, with 1 being worst practice and 5 being best practice. At the bottom end, Australia and Canada look quite similar: a fat tail that has just short of 50 per cent of firms in each country scoring a 3 or less, meaning that management practices in these firms are no better than mediocre. In the US only a third of firms score this low.

At the top end however, there’s a lumpiness in Australian management practices that sees capabilities tap out somewhere between “OK” and “not quite stellar”. Fewer than three per cent of Australian firms are considered to have near-to-best management practices (a score of 4 or above), compared to 9 per cent of Canadian firms and 11 per cent of American.

Distribution of management practices score, 2004-2014

Notes: Aus n=451, Can n=148, USA n=953

Source: WMS.

These distributions beg a number of key questions of the policy environment. The two most important, are 1) how come it’s easier for laggards to survive in the Australian and Canadian markets than in the US? And 2) why are Australian firms missing from the frontier? Neither are likely to have easy answers.

Post script: All of this data is old, and unfortunately includes just the manufacturing sector. The ABS’ Management Capability Survey released at the end of last year will help to give an update and shed light on the broader economy.

Leave a comment