The first industrial revolution was a comprehensive technological, cultural, social and economic overhaul. The technologies and processes introduced during the late 18th Century brought with them lasting changes in how society organised.

Industry 1.0 welcomed machine production, steam power and the factory system. Each of these technologies displaced labour in some form or another.

However, while these machines were labour-saving, they were also highly productive. As output increased, prices fell. This stimulated demand and generated a need for more workers. Entirely new jobs were created to oversee the machines, and later, as companies got bigger, managers, accountants and other support staff were added to the mix.

It was a major turning point in history. It marked the start of an unprecedented run of sustained economic growth.

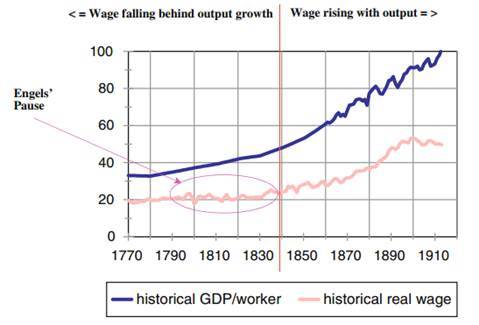

But, it took some time to get going. Production increased slowly at first, output per worker grew roughly 6 per cent per decade between 1780 and 1840). But would start to rise more rapidly thereafter, 10 per cent per decade until 1900.

Wages however, basically stayed flat for the first half of the 19th Century. In the 60 years between 1790 and 1840, real wages only increased by 12 per cent.

This period of benign wage growth is known as “Engels’ Pause” (named after Marx’ co-author, Friedrich Engels).

Growth in output per worker and real wages, 1770-1920

Source: Allen 2007.

During Engels’ Pause, wages stagnated and living standards deteriorated. Wage growth decoupled from productivity growth. Income inequality increased. Profits surged, but were generally not reinvested. And the share of income accrued by capital rose; and by labour fell. It was a period pervasive labour-market upheaval as some jobs vanished, others changed beyond recognition and totally new ones emerged.

It’s a story that sounds eerily familiar.

Each wave of new technologies introduced since the first Industrial Revolution has had a similar (although but perhaps not as dire) impact on the economy. Are things different this time? Perhaps.

It’ll probably all be faster this time. Technologies are reaching ubiquity much more quickly than they ever did. It once took 45 years for an invention to become global; but the Internet achieved this in just seven. Telephones needed 75 years to get to 50 million users; Angry Birds took just 35 days. WhatsApp only took six years (700 million followers) to do what Christianity needed 19 Centuries!

The speed of the change poses a number of challenges to institutions, which will need to keep pace. But generally, the economy has proven quite adept at dealing with — and taking advantage of — new technologies. The 19th century experience of industrialisation suggests that jobs will be redefined, rather than destroyed; that new industries will emerge; that work and leisure will be transformed; that education and welfare systems will have to change; and that there will be geopolitical and regulatory consequences.

Where it might be different, is in regards to what the technology is displacing. Most of the discussion on this issue so far has been about technology substituting for labour. Critically though, the digital economy allows many goods and services to be codified. Once their codified, they can be digitised and replicated — at virtually zero cost — and transmitted anywhere in the world.

Now we’re all of a sudden in a world where digital technologies are substituting for capital. “In the digital age, innovators and entrepreneurs, not workers or investors, will be the main beneficiaries.”

Leave a comment