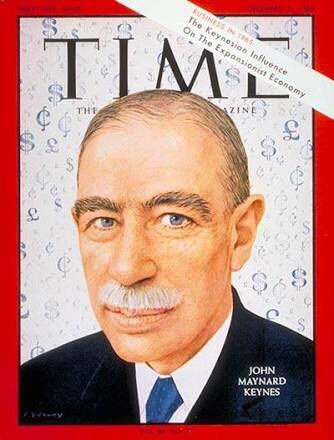

After marvelling at the rate of technological progress, Keynes predicts — in a gorgeous piece of 1930s economic prophesising — that mankind will have solved its economic problem and the new challenge will be to figure out what to do with all our spare time. We will be:

“…afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come — namely, technological unemployment.”

Almost 100 years on, we are now very much aware of the concept of technological unemployment.

The basic idea is that the more work that is given to robots, the less that will be available for everyone else, and this will ultimately lead to unemployment. (Similar arguments are used to oppose trade and migration.)

The problem with this argument though, is that is assumes there is only a fixed lump of work to be done.

Lump of labour thinking fails to recognise how productivity growth leads to job creation. Productivity gains in the form of process improvements lower production costs. Lower production costs lead to lower prices. Lower prices stimulate increases in demand. Greater consumption encourages greater production. And more production means more jobs.

Ultimately, automations that economise the use of labour will increase the demand for labour in the long run. These jobs will probably be different, but there will nonetheless be more of them.

To be fair to Keynes, he wasn’t a subscriber to the lump of labour fallacy. Rather, he described technological unemployment as a temporary phenomenon — a phase of maladjustment caused by “the discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour.”

So far, history has shown that we’re pretty good at finding new uses. The first industrial revolution for example, did not eliminate the need for human workers. On the contrary, they created employment opportunities sufficient to soak up the 20th Century’s population explosion. In the 1920s, passenger cars displaced equestrian travel, but it gave rise to the roadside motel and fast food restaurants need to serve the motoring public. The diffusion of ATMs lowered banks’ operating costs and freed up clerks to provide more complex services to customers — resulting in an increase in employment in the banking sector. Drones may disrupt the transport and delivery sector, but someone will have to install and service all the drone nests needed to accommodate them.

Keynes’ essay on the Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren gets most of its notoriety for the following:

“…we shall endeavour to spread the bread thin on the butter-to make what work there is still to be done to be as widely shared as possible. Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour work week may put off the problem for a great while.”

At first glance this reads like one of those “I think there is a world market for about five computers” type comments, but when you look at the numbers, it’s not too far off the mark.

Compared to life at the turn of the 20th Century, things in 2017 are pretty great. Today, 62 per cent of people have a job, a third of which are employed only part time. Nine out of 10 persons aged 65+ are out of the labour force. 20 per cent of adults are studying. Plus we have generous annual and personal leave allowances. When you average it all out, the average Australian is working only slightly more than what Keynes promised — 20 hours a week, 4 hours a day (total hours worked / persons aged 15+, 5 day work week) — and from this, we’re able to generate incomes of about $60,000 per person. Not bad.

Leave a comment