In 1968 a bunch of learned minds wrote a book about what technology would look like some 50 years hence. The book, Toward the year 2018, prophesised rapid improvements in the speed of transportation, the ability to control the weather, disintegrator guns, anti-gravity technology (flying cars), picture phones and a nine hour work week.

Some things they got right. But of course, most things they got hilariously wrong. To be fair, predictions are hard to get right, especially when about the future.

One thing they didn’t predict was the exponential growth in the number of learned minds that would still be trying to predict the future.

Techno-foresighters fall into two camps: the techno-optimists and the techno-pessimists.

Leading the memory-card-half-full crowd are Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson (and the Economist). McAfee and Brynjolfsson have written e-books with titles like The Second Machine Age and Race Against the Machine. Their argument is that when it comes to technology: haven’t seen anything yet. The advances in robotics, AI, machine learning, additive manufacturing autonomous vehicles etc are about to fundamentally overhaul production and launch us into a fourth industrial revolution. We should embrace these developments, they argue, and learn to work with machines. (Watch this hypnotic video of Amazon’s warehouse droids if you’re unconvinced.)

Leading the memory-card-half-empty camp are Robert Gordon and Tyler Cowen. Their hard cover books are much less sanguine; they have titles like The death of innovation, the end of growth and How America Ate All the Low-Hanging Fruit of Modern History. Gordon likes to play a game wherever he goes called “Find the Robot”. As he goes about his everyday life he looks for machines performing tasks that humans once handled. Most of what he sees doesn’t impress him: ATMs, self-checkout kiosks, and boarding pass scanners have been around for years. Beyond that, he argues, not a lot has changed. People “do the same thing that they did 10 or 15 years ago. In office situations… going into retail stores, going into restaurants. …a large part of the economy [is] operating in the same way as it did last year and the year before.”

Regardless, of whether we think technology is changing fast or slow, or if innovation is alive or dead, what we can all agree on, is that there has been a change in how the gains from technology are being distributed across the economy.

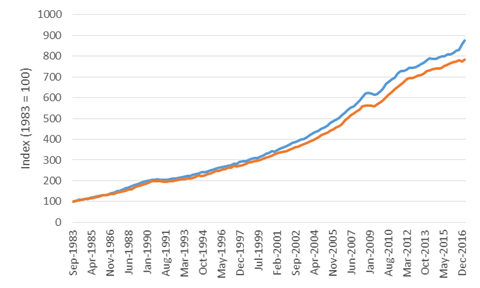

GDP per capita, labour productivity, employment and median household incomes rose in almost perfect lockstep in the decades after WW2. Job growth and wage growth kept pace with gains in output and productivity. Things got a bit bumpy in the 90s, and have now seemingly decoupled. GDP and productivity, have remained on an upward trajectory, but the income and job prospects for typical workers have faltered. In the chart below, we can see a widening gap in the growth of total output and the growth of income paid as to workers. The labour share of income has fallen from about 52 per cent in 1983 to 46 per cent today.

Growth in GDP and wages

Note: Index based on current prices

Source: ABS

At the end of the day, we don’t know what the future has in store. The best way to respond to change is to roll with the punches: adapt, react, anticipate, innovate. To that end, what’s concerning is not how fast technology is progressing, but rather how dynamic and responsive is the economy. If worrying trends in business dynamism and labour fluidity continue, then this may hamper our ability to reap the full gains of the coming technological revolution (if there is one).

Leave a comment