“America has lost nearly one-third of its manufacturing jobs since NAFTA and 50,000 factories since China joined the World Trade Organization.” (D. Trump)

Populism and protectionism are back in vogue. Anti-trade, economic-nationalist sentiments are shaping elections across the globe.

And it’s easy to sympathise. Manufacturing employment in Australia has fallen by about 10 per cent (112 thousand jobs) over the past 30 years. In the US, the drop has been much more dramatic, where the decrease has been closer to 30 per cent. That’s over five million jobs — all of which are wrapped in identity, tradition and history.

If it weren’t for trade, the argument goes, then these jobs would still exist.

It’s easy to point out the flaws in this argument. By specialising in those areas where we have a comparative advantage and trading for those goods and services where we are less productive, we are able to maximise our incomes. (Ricardo’s theory of comparative advantage turned 200 this year.) The shift away from traditional manufacturing has allowed us to focus on higher valued activities — like finance, health care, tourism, METS, resources and advanced manufacturing. We’ve been able to create many times more jobs in the process, as well as enjoy significant increases in GDP as a result (how these benefits are shared is a different story).

Besides, the argument goes, it wasn’t the Chinese that stole our jobs, it was the robots.

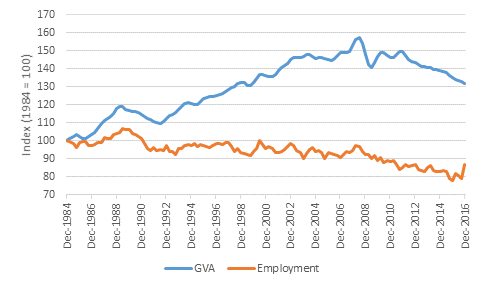

Technological progress has been destroying jobs for centuries. Blacksmiths, typists, checkout operators, bank tellers, bookkeepers and paralegals weren’t offshored, they were automated. While perhaps not necessarily more prevalent than other industries, automation in the manufacturing sector has at least been more visible. The sector has been boasting about their advances labour saving technologies like robotics, AI, 3D printing, and Industry 4.0 for years. Automation has allowed for manufacturing output to expand, while employment has decreased (see chart below).

Index of manufacturing output and employment, 1984-2016

Source: ABS

Efforts to blame shift the discount towards innovation and technology enters some very tread-lightly, potentially reckless territory.

The staple comeback that the pro-traders use to sway the rust belt is the iPhone. Without trade, iPhones (and everything else we import) would cost much much more. One study estimates that if an iPhone were manufactured and assembled in the US, it’d cost about 20 per cent more. You like having a cheap iPhone? Then you like trade.

But the iPhone is actually a much stronger defence of innovation than it is globalisation. The no-technological-progress equivalent of the locally built iPhone would be to hold technology constant at 1950 levels. (which is about when we effectively had no trade with China). Back then, it would have taken the world’s entire stock of supercomputers — about 40 Univac 1s — to match the computing power in an iPhone, at an approximate cost (40 x $1 million = $40 million, inflated to 2017 dollars =) $386 million. You like having a cheap supercomputer in your pocket that provides you with access to almost every media ever created? Then you like innovation.

As many jobs as technology has destroyed, it has created many millions more. Sure we now have a few thousand ap developers, computer programmers and data journalists. But more importantly we also now have hundreds of thousands of baristas, yoga instructors, dog walkers, financial planners and occupational therapists. These jobs only exist because improvements in technology have increased our incomes sufficiently that we are now able afford these products.

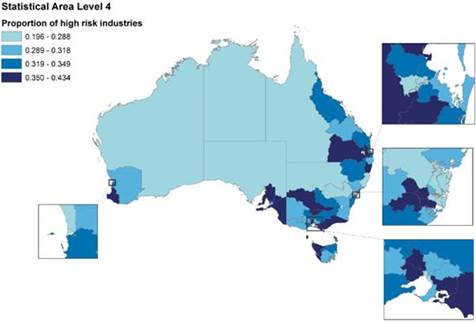

Post script: I wasn’t quite sure how to weave this into the story above, but it’s one of the more telling charts I’ve seen in a while and didn’t want to leave it out. It’s a heat map of regional employment in highly automatable industries based on an earlier OCE research paper.

Proportion of employment in industries with high risk of automation

Source: Based on Edmonds and Bradley 2015.

Leave a comment