Australia is the world’s largest producer of spodumene. We produced about 500kT last year, about three times as much as we did a decade before. All of this was shipped to China where it was turned into lithium-carbonate, -hydroxide and -chloride, the principal ingredients for making lithium batteries.

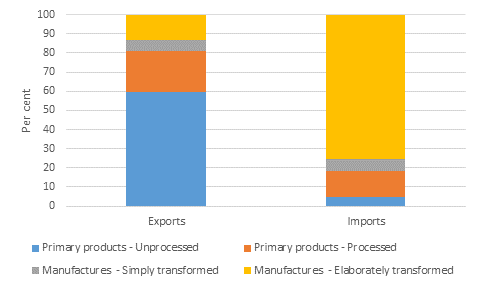

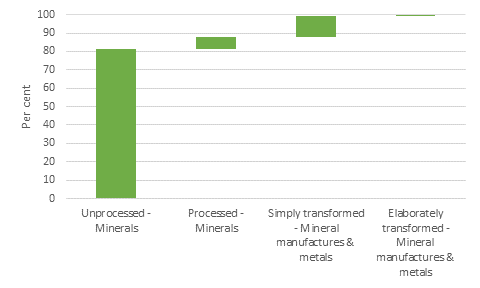

A bit of an outlier in the OECD, Australia’s exports are heavily weighted towards unprocessed primary products (60 per cent of all exports). A figure that’s even more pronounced when we look at the minerals exports — about 81 per cent. Beyond the initial resource (which is a substantial part of the value chain), we don’t really add much value to our commodities.

Composition of trade, 2016

Composition of minerals exports, 2016

Notes: There’s a quantum of “other” exports and imports that’s been excluded here.

Source: http://dfat.gov.au/about-us/publications/Pages/trade-statistical-pivot-tables.aspx

Reflecting this, we often hear calls for the development of downstream industries. Not just in the resources sector, but generally across the economy we need to reposition our industrial structure to capture more value along the supply chain. After all, a tonne of batteries sells for way more than a tonne of spodumene.

It’s a good question — are we missing out?

Australia is in a unique position where we are long on resources and short on people in a region that’s short on resources and long on people. Add to this: the fact that our mining sector is filled with companies that are world leaders in data analytics, autonomous vehicles, operations optimisation and innovation; that our labour and energy costs are significantly higher than those faced elsewhere; and we typically have tighter regulatory regimes and environmental controls.

So we make things that are resource-intensive, and buy things that are labour-intensive. We export those raw commodities that we have a comparative advantage in, like iron ore and coal, and import “elaborately transformed” manufactured products like computers and cars where we have a comparative disadvantage.

We can actually measure our comparative advantage using a metric called Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA). In short, RCA calculates how much a country is punching above its weight for a given product. A RCA is greater than 1 reveals a comparative advantage for that product; and a comparative disadvantage if less than 1. For example, Australia’s RCA for mineral ores is 25.2, which implies we are exporting 25.2 times our “fair share”. For aluminium, its only 1.6. And for something like shoes its 0.05.

The chart below plots the growth in RCA against the growth for our top 40 exports over the past decade. What we’d expect is that those areas where we are most productive (ie we have a comparative advantage) should be where we’ve been most successful. And that’s exactly what we seen in the chart.

Annual change in export growth and revealed comparative advantage, 2006-2016

Source: https://comtrade.un.org/

The reason why you can’t trust an economist that mows their own lawn is because it shows that they clearly don’t believe strongly enough in the principle of comparative advantage. Countries, like people, gain the most when they specialise in the things they’d are best at, and trade those for the things they are not. The short answer for Australia doesn’t participate much downstream, is that it’s too costly. It’s not that we’re missing out on value in the value chain, but rather moving along the value chain would mean shifting (economic) resources away from doing the things we’re good at and placing them in activities that others can do better.

Leave a comment