For the last few Budgets, Treasury has predicted that things will get worse before they get (a lot) better. Compared to last year’s budget, real GDP growth has been revised down for 2016-17 and 2017-18; unemployment is expected to be a bit higher for a bit longer; and wages won’t grow by as much.

But then things will take off (and revert back to the average)! Growth in non-mining business investment is tipped to triple next year, unemployment will drop, wages will rise and growth will return to levels (3.0 per cent) we haven’t seen for about a decade.

There’s an industry saying that says, there are two types of forecast — wrong ones and lucky ones. No one expects forecasts to be right all of the time of course. Swings in key variables can be hard to predict and can have a big impact on the Budget’s bottom line — think commodity prices. Typically, the Budget underestimates as the economy improves and overestimates as things deteriorate.

Over the cycle, you’d expect there to be a bit of over and under, but those errors should balance out.

Since the GFC however, the Budget has systematically overestimated how much the economy will grow and how many revenues the Government will collect. This can be seen in the chart below.

Budget forecasts of tax receipts growth

Source: The 2017-18 Budget, page 8-8.

The consistent positive bias in recent years is worrisome. The Economic Society of Australia (ESA) recently ran a poll, where they asked prominent Australian economists: “should the government outsource economic forecasting?” (In typical economist fashion, the response to the ESA poll was “well it depends”.)

It’s not an unheard of proposition — there are currently about 40 countries around the world that make use of independent, public, fiscal councils to perform this function. But the difficulties that befall the Treasury however, might actually be common to all attempting this task, public and private.

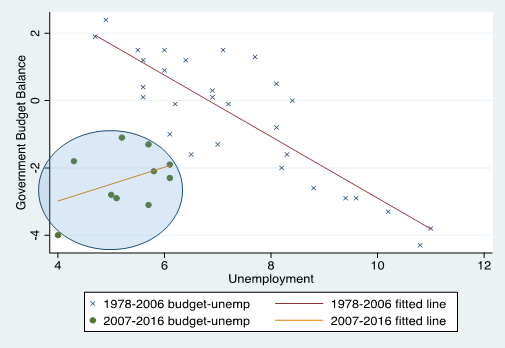

Bob Gregory presented the chart below at this year’s Freebairn Lecture at the University of Melbourne. It shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and the Budget bottom line. Between 1978 and 2006 the relationship is pretty consistent. It is also what you might expect — when unemployment is high, automatic stabilisers kick in and spending increases. When unemployment is low, the reverse happens and spending decreases.

Unemployment and the budget balance

Source: Gregory 2017.

Since the GFC however, the relationship between the Budget balance and unemployment has seemingly decoupled. This must make it very difficult to forecast things like income tax, GST, welfare payments, investment and GDP.

Gregory suggests that this is a sign that the economy is doing much worse than we might think. For example, if you were to look at various labour force data, the initial shock of the GFC doesn’t really show up. At least not to the extent that previous recessions did. Neither does the recovery. There hasn’t really been a rebound from the GFC, just a slow and steady decline for the best part of a decade.

Recent reviews of forecasting methods by the Treasury and the RBA’s have highlighted difficulties of accounting for structural changes or persistent shocks. Moreover, the presence of “persistent errors being made in Treasury’s forecasts” would appear consistent with notions of a new norm.

Any expectations that we will grow ourselves back to surplus may be met with disappointment. A more certain solution to fiscal woes would appear to lie in structural reform.

Leave a comment