Almost one in every two dollars spent at a coffee shop in the United States is at a Starbucks. And if you’re not spending it there, then you’re probably buying a Blueberry Latte from Dunkin’ Donuts. Combined those two conglomerates control 65.4 per cent of the American coffee market.

The Australian café scene by comparison, is far more competitive. The largest operator in Australia only has a 5.1 per cent market share.

Against this background, it shouldn’t be a surprise that Australian coffee just doesn’t taste better, but seems to be a better product altogether. Competition empowers consumers to shop around, to be picky and demand better coffee. When there is only one offering, consumers only have a choice between buying and not buying (and sometimes not even that if you think about parts of health care, education and utilities). But when there are “many” firms, consumers are able to vote with their feet and choose the product that meets their needs the most.

This pickiness has been accelerated by new digital technologies and platforms — think QR codes, TripAdvisor and Yelp. Digital platforms have provided consumers with a new understanding of speed, the brand relationship and personalisation, and these new levels of expectation and standards of customer experience have upended traditional business models.

By empowering consumers in this way, competition breeds choice and innovation. In those markets where competition is high, firms must fight for the consumer’s dollar. They do this by finding ways to lower prices or by somehow differentiating their product. Heightened consumer savviness creates the demand for businesses to innovate.

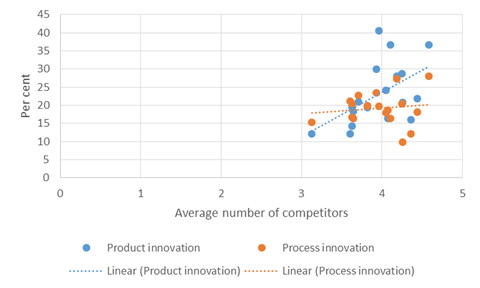

The relationship between competition and innovation is made clear with data from the ABS’ Business Characteristics Survey. The chart below plots the proportion of innovative firms in each industry against the “amount of competition experienced”. The majority of firms (62 per cent) indicated that they experienced competition from more than five firms, but this varies from industry to industry. For example, whereas 83 per cent of firms in the financial services sector indicated that they competed with more than five firms, this was the case for only half of mining firms. At the other end of the scale, 13 per cent of firms indicated that they faced no effective competition — the lowest being wholesale trade (5 per cent) and the highest agriculture (34 per cent). Industries with a higher level of competition were more likely to report innovation — particularly so for product innovation.

Innovation-active businesses by number of competitors, by industry, 2013-14

Notes: Average number of competitors is estimated by using the midpoints of range. A more thorough analysis was conducted in 2011 by our very own Tala Talgaswatta.

Source: ABS BCS, 2013-14

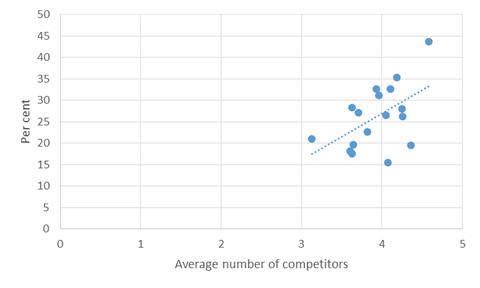

A similar result can be seen for firms that reported an expansion in the product range. Roughly a quarter of businesses reported an increase in their product range over the last 12 months — the most being in the wholesale trade (44 per cent) and the least in rental and hiring services (16 per cent). The data suggests that the more competition a business faces, the more likely they are to offer new products.

Firms that increased their product range by number of competitors, by industry, 2013-14

Notes: Average number of competitors is estimated by using the midpoints of range.

Source: ABS BCS, 2013-14

So, is the answer to our innovation problems a simple matter of ever-increasing competition? Probably not. A certain amount of market power is required to make investments and take risks in R&D. But there has to be some optimising point — beyond which any further increases in competition are likely to be harmful to innovation.

And we don’t appear to be there just yet. Sure our café scene is more competitive than in the US, there are other areas where we lack competition. For example:

· The top three supermarket chains in the US share 31 per cent of the market between them; while in Australia Woolworths and Coles and 63 per cent.

· The big four banks control 70 per cent of the Australian market, compared to 48 per cent in the UK and 33 per cent in the US.

· The top four internet service providers in Australia control 95 per cent of the market, compared to 65 per cent in the US.

What is particularly troubling is the extent to which this is materialising as consumer complacency. The recent Nielsen Global New Product Innovation Survey found that while around the world, consumers have a strong appetite for innovation, the appetite of Australian consumers was far less. Only 37 per cent of Australian consumers had purchased a new product in their last grocery shop, compared to 57 per cent of global consumers. These result ring true across a number of indicators included in the survey.

While the answer might not be about simply increasing competition, there does seem to be something to be said for investing in making better consumers.

Leave a comment